In California, a state built on the idealism and tacit cruelty of real estate capitalism, no one is innocent.

That’s no different with Airbnb and Proposition F, merely the latest of San Francisco’s Brobdingnagian sagas over land-use politics that will go down in today’s election.

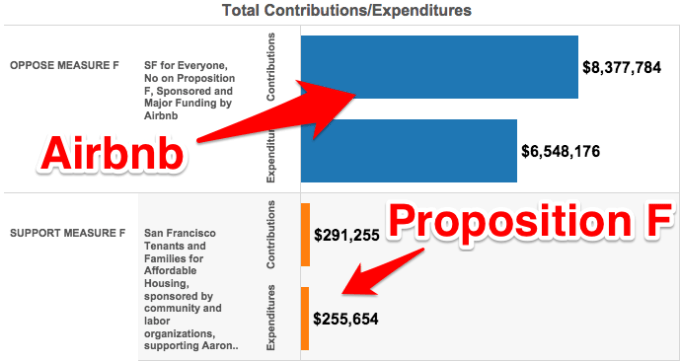

Spending north of $8 million to defeat the measure, Airbnb’s effort has blanketed local TV stations with ads at a ratio of 100-to-1 against Proposition F. This weekend, campaigners went door-to-door to “reverse trick-or-treat” by handing out adult coloring fliers and Halloween-themed crayons in addition to the 236,413 door attempts, 226,597 phone calls and 2,016 window signs posted as of Sunday.

This is not to mention the head-scratching billboards trumpeting the $12 million in taxes that Airbnb guests pay to the city each year, which the company quickly ripped down amid a public uproar.

Pushing Proposition F on the other side is is an unlikely coalition of affordable housing and tenants rights activists, property owners and politicians whose decades-long careers and lives have intersected with some of the city’s most landmark planning decisions — from the downzoning of residential neighborhoods to rent control to limits on the pace of high-rise office construction.

Who is right?

Both the current system and Proposition F are flawed in different ways.

Under the current law, Airbnb gets all the nicely scalable parts of being a laissez-faire software platform where hosts easily list and de-list properties while absolving itself of any responsibility if hosts happen to remove units from the city’s housing stock. Each unit lost to commercial short-term renting costs the city somewhere between $250,000 and $300,000 a piece, so a few hundred units easily adds up to a hundred million dollars or more in impact.

Then the city gets all the excruciatingly unscalable parts of enforcement — like holding hearings, investigating neighbor complaints, compiling testimony from witnesses, issuing and collecting fines — with just four people who have little visibility or accurate data into how the market is behaving because companies like Airbnb have refused to share data while only 7 percent of hosts have registered with the city.

On the other hand, Proposition F is a ballot initiative, which can only be amended by another popular vote. It’s an inflexible kind of regulation that is badly suited for a dynamic and fast-changing market. Proposition F also leans on the threat of neighbor-to-neighbor litigation in which residents are entitled to civil penalties, which could chill the entire market.

Overall, land-use and housing in San Francisco is governed by this teetering Jenga tower of regulations that has been painstakingly erected block by block over decades and that is precariously balanced between tenant and property-owner interests.

Airbnb and the growth of tech in San Francisco have disturbed that balance. The San Francisco Bay Area’s land-use laws and governance structure aren’t built to handle the speed, scalability or income distribution of the modern technology industry and the capital that flows through it. And yet, it’s unreasonable for the company to put all of the blame on the city for not building housing fast enough, while taking no responsibility for compounding the problem.

Airbnb may be transformative for the tourism industry, but it amplifies and feeds into — rather than disrupts — the deeply problematic structure of the American housing system.

How The Regulatory Process Happened

Until last year, the legislative arm of the city government allowed Airbnb to grow largely untouched until David Chiu, now in the California State Assembly, made a first pass at regulation last fall.

But Airbnb actually began lobbying city supervisors way before there even was a bill back in 2011 through Alex Tourk, who went on to become managing director of Airbnb investor Ron Conway’s non-profit sf.citi. That was beginning of around 200 lobbying meetings with the city government over four years.

Unhappy that the first version of the law passed last fall was too lenient, a coalition of affordable housing activists and property owners — who sometimes oppose each other — threatened to do a ballot initiative last year.

Citizens in the state of California have the ability to bypass the legislature and create their own laws. This dates back to the Progressive Era in the early 20th century when reformers were trying to break the corrupt hold of the railroads, Southern Pacific and tycoons like Leland Stanford over the California state legislature. In San Francisco, it takes 9,700 valid signatures or so to get an idea on the ballot. Then, once an initiative is passed, the only way to change it is to go back to the ballot.

At the last minute last year, the coalition pulled back their initiative because they didn’t have enough money to do a full campaign and they hoped the city would tighten the law this year.

So over the summer, Supervisor Mark Farrell, a moderate, led a second pass at the short-term rental regulation to try and forestall a ballot initiative with Mayor Ed Lee’s support. It was a tougher proposal with a 120-day cap across the board and a private right of action for neighbors within 100 feet of any property. In the city’s current law, neighbors have the right to file suit in civil court against hosts but they can only win attorney’s fees, not other penalties.

“What is worrisome to us and what the coalition is pushing is regulation that might create a new cottage industry of fly-by lawsuits,” Farrell’s legislative aide Jess Montejano told me back in April, echoing the concern that host and San Francisco resident Eric Meyerson raised in two Medium essays that went viral over the past month.

Still, the revised law wasn’t tough enough for the liking of Prop. F’s backers. The 120-day cap didn’t make it because the Board of Supervisors didn’t have enough votes to pass it.

So it reverted back to the older system, where hosts can either do 90 days where they’re not present, or host an unlimited amount of days if they’re there. The planning department has said this distinction is hard to enforce, because it’s difficult to prove night-by-night whether a host was there or not.

“I don’t believe true enforcement can happen without penalties. If there is nothing to compel you to stop lying, why would you?” said Jennifer Fieber of the San Francisco Tenants Union. She said the tenants union turned in seven cases under the old regulation. But because the listings had disappeared by the time of the hearing, the Department of Building Inspections could not issue a notice of violation. “Their rulings were Kafka-esque,” she said.

Dissatisfied with the Board of Supervisors’ changes, the group moved forward with their initiative.

Who Is Behind Proposition F?

Unlike what Airbnb investors like Paul Graham have argued, the hotel industry hasn’t really been at the center of the city’s regulatory conversation. They only started piling in during the last few months. Hotels in San Francisco are on pace to have the highest occupancy rates in the United States this year, and it turns out Airbnb is not really eating into hotel market share so much as it is growing the overall market. I’ve watched months of testimony before the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors, and I can’t recall a time I’ve seen a representative of the hotel industry.

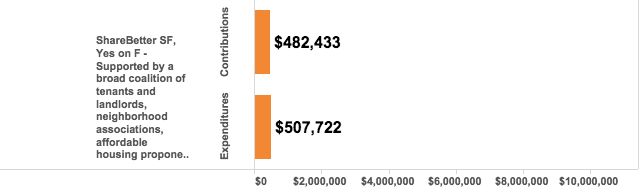

Instead, the bulk of donations to the Prop. F campaign — about $390,000 worth — came from the hotel workers union, which represents cleaners and service workers earning a median income of $30,000 per year. A few hotel industry checks have come in during the two weeks with $25,000 from the Hotel Association of New York City and $49,000 from the American Hotel & Lodging Association.

But all of this pales in comparison to the more than $8 million that Airbnb is spending to defeat the measure.

Instead, the people at the center of Proposition F are a rather familiar cast of characters when it comes to San Francisco land-use politics.

The trio behind Proposition F, Dale Carlson, Doug Engmann and Calvin Welch, were behind 1986’s Proposition M, which capped the amount of office space that can be built in any given year in San Francisco. With San Francisco office rents now at record levels, the regional tech industry is now spilling over into Oakland where it will impact and probably displace working-class communities there, especially with the expected entrance of Uber in 2017.

As a young Haight-Ashbury activist in the 1970s, Welch was involved in the first residential downzonings across San Francisco and tested former Mayor George Moscone’s electability by seeing if he would take a hit off a blunt.

Both Welch and Engmann are of the school of thought that supply and demand don’t really matter for affordable housing in San Francisco. Here’s Engmann, who sold a Pacific Heights Queen Anne Victorian for $23.889 million in March, explaining why trickle-down housing doesn’t work in a video.

Welch, meanwhile, lives in a Haight-Ashbury duplex that is comfortably tax assessed at a 1976 value of $57,010 while being worth $2 million at current Zillow estimates. Here in this video, Welch explains how more housing production increases prices.

Airbnb is a funny issue because it literally twists people and interests into pretzels. Proposition F has generated all kinds of unthinkable alliances on the issue.

You’ve got the San Francisco Apartment Association representing landlords, and then the San Francisco Tenants Union on the same side. You’ve got progressive David Campos, who is a supervisor representing the working-class Latino community of the Mission, and U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, who was a pro-business and pro-landlord mayor of San Francisco in the 1980s, both backing Proposition F.

With San Francisco office rents now at record levels, the regional tech industry is now spilling over into Oakland where it will impact and probably displace working-class communities there.

Then, Airbnb has put up the bulk of an $8 million campaign to defeat Proposition F. Airbnb has hired experienced local political operators, including David Owen, who spent five years working for progressive Aaron Peskin, the former president of the Board of Supervisors. Peskin, who is running again in District 3, was known for threatening, late-night drunk dials and blockading development in North Beach. But he and progressive supervisor Chris Daly also brokered some of the high-rise development deals that enabled SOMA to be the nucleus of startup activity that it is today.

After Peskin’s opponent, Julie Christensen, weakened the caps on the existing short-term rental law this summer, her campaign received donations from Airbnb investors like Sequoia Capital partners Jim Goetz, Roelof Botha and Alfred Lin along with other tech notables like Sean Parker.

On top of all of the billboards and that embarrassing ad campaign, SF for Everyone, the community group backed by Airbnb, is organizing extensive precinct walks and has partnered with labor union organizers and spokespeople for SEIU like Alfredo Fletes.

The alliances are strange. But regardless of whether Proposition F passes or not, ballot initiatives are a wedge that can push regulation in a certain direction.

Indeed, the threat of Proposition F forced the mayor’s hand. The city opened an Office of Short-Term Rental Administration & Enforcement over the summer to toughen up enforcement. Up until this summer, there were only a couple cases of serious enforcement, where the city attorney sued and fined hosts who were illegally working with platforms like VRBO after evicting disabled tenants.

How Does Enforcement Work Today?

Hilariously, even though the No on Prop. F campaign centers its messaging on “spying,” the current enforcement process relies almost wholly on “spying” or complaints from neighbors. Here are 10 of the city’s 13 enforcement actions here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here. All are in response to complaints.

Less than two months ago, Kevin Guy got hired for the head job of the new short-term rental enforcement office. An urban planner who worked on the $4.5 billion Transbay Terminal project, he and three other enforcement officers on loan from the planning department must somehow determine which of the 5,000 to 10,000 listings are legal.

Because Airbnb has declined for years to provide data that would help the city government identify units that have been permanently taken out the housing stock, the office has to do this in the dark. They respond to complaints (or “spying”) from neighbors and by manually filing through online listings to see if they have a registration number or a lot of reviews.

“We can take a look at the listing and see the number of days that appear to be booked through reviews. We don’t necessarily have exact certainty on the accuracy of the reporting but we want to presume some amount of good faith that people are reporting correctly,” Guy said. “But if we receive complaints that don’t seem to align with the number of nights that are stated as bookings, that would be a trigger for us to do an investigation.”

Next year, hosts will have to file quarterly reports with the city and the office will expand to six people.

So far, about 730 hosts have registered with the city, according to Guy. That’s compared to the 9,692 listings that Airbnb said it had on and off in the year ending on April 30. The city requires in-person meetings for registration because it turned out that a small, but significant, number of applicants had no legal right to host in the spaces they were listing.

A more senior planning department official told me a few months ago that “data provided voluntarily by platforms would be helpful to the public and in the self-interest of the tech companies.”

If the city mandated that Airbnb turn over data, it’s possible there would be an expensive lawsuit under data privacy laws, something the city isn’t willing to use its limited financial resources to fight. The other platforms, like HomeAway, have already tried to litigate against the existing regulation because they feel it is too tailored to Airbnb’s business.

Alternately, the planning department said it didn’t need access to Airbnb’s data so long as every host registered and platforms refused to list unregistered units. But the Board of Supervisors didn’t have enough votes to pass this.

Throughout the process, Airbnb has insisted that it is the city’s responsibility to enforce its own laws, and that regulation should be designed for the whole industry, not just one company. Airbnb has said it is impossible for it to monitor the listings of the more than 30,000 cities that it operates in, and investor Ron Conway said at Disrupt NY last spring that data-sharing with the city on hosting activity would be akin to NSA spying.

The nascent enforcement office has tried to step up in the last few weeks by issuing $355,000 in fines on 13 decisions out of 221 complaints the city has received since February.

“If someone feels like they’re flying under the radar and operating when they’re not under registration, the fact that we are taking these cases to administrative hearings and assessing pretty substantial penalties should be an incentive to come in,” Guy said.

Three years after it started lobbying the city government, Airbnb agreed to start remitting taxes on behalf of hosts to the city last September. It says that it sends about $1 million per month into government coffers. But because of privacy regulations, the tax collector and and the office of short-term rental enforcement can’t share data with each other.

How Is Airbnb Affecting The Housing Stock?

According to Airbnb: 348 units were rented more than 211 days last year, or the level at which the company said a unit would be more profitable as a short-term rental than a full-time apartment.

According to the Legislative Analyst’s Report: 925 to 1,960 units may be taken out of the housing stock. The lower end of the estimate defines commercial hosts as people who host more than 90 days a year, while the higher end of the range defines commercial hosts as people who put their units out for more than 58 nights a year.

According to city economist Ted Egan: The report didn’t say. But Egan did add that a host would need to do somewhere between 123 to 241 days of hosting per year to earn more than a long-term rental. Each unit removed from the housing stock would have a net negative economic impact of a $250,000 to $300,000 loss to the city.

According to the San Francisco Chronicle: At least 350 units appeared to be full-time short-term rentals.

In Europe, Airbnb is professionalizing much more out in the open than it is in the U.S. In the U.S., Airbnb likes the idea that people are renting out their own homes.

There is a Southern California-based company called Airdna that advises property owners on how to maximize their Airbnb rental income stream. They scrape Airbnb’s site every day unlike the San Francisco Chronicle report, which scraped only a single day’s worth of data. The company says its software also scrapes for whether a room is available, blocked or booked. As such, it can estimate revenues instead of guess-timating from the number of reviews.

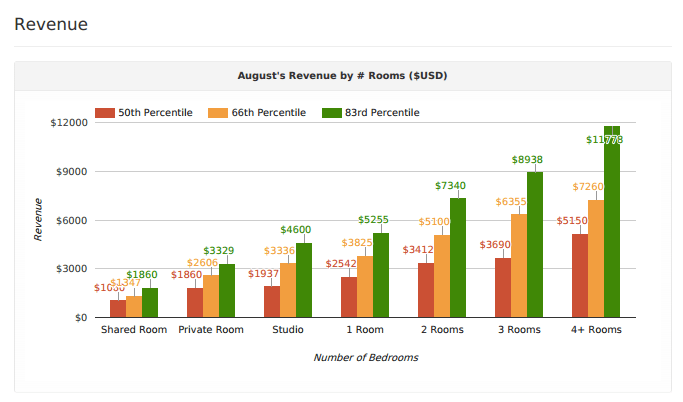

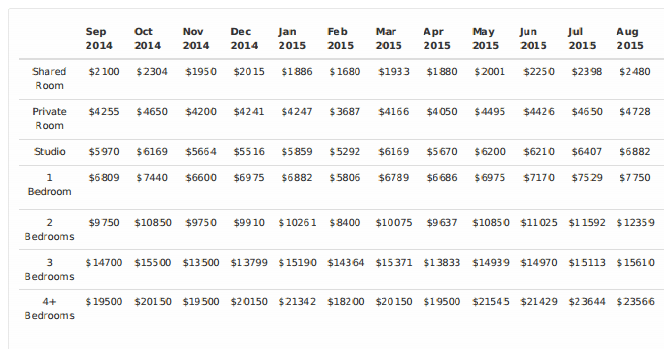

Airdna’s data suggests that what Airbnb says is technically true — that most hosts are renting out their spaces occasionally. The median revenue per listing is less than market-rate rent at every apartment size.

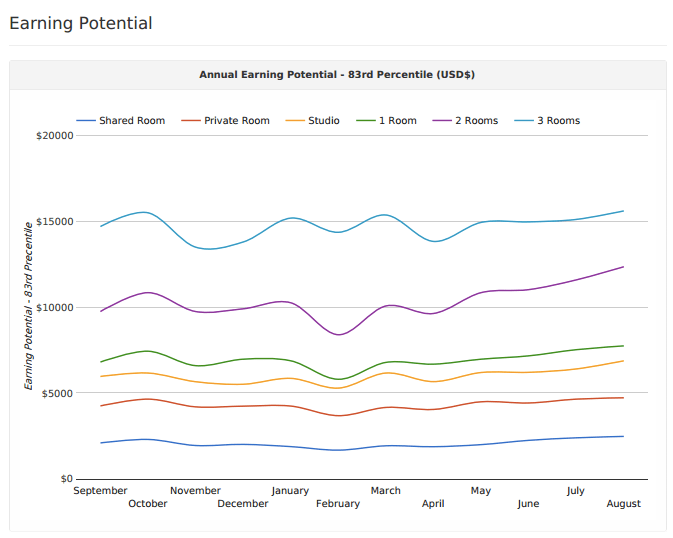

But at the high end of the range, Airbnb looks like any other two-sided marketplace business — a cohort of power sellers dominates. A one-bedroom short-term rental in San Francisco performing at the 83rd percentile of listings could earn anywhere from $5,800 to $7,800 per month, according to Airdna’s data.

Airdna, a Santa Monica-based company that advises property owners on how to maximize their Airbnb rental revenue, calculated median August revenues for hosts in San Francisco.

If you’re in the top one-sixth of hosts, here is what Airdna estimates you might be able to earn in San Francisco’s market. It’s way above what market-rate housing for permanent tenants commands.

Airbnb didn’t comment on the accuracy of Airdna’s data, except to say, “When it comes to our people to people platform, our focus is on working with our Hosts, where the majority are middle class people looking to share their home to supplement their income, and seeking to partner with cities to put in forth common sense approaches to home sharing.”

Internally, Airbnb engineers have told me they know that Airdna is scraping their platform every day.

However, even with this level of data granularity, Airdna said it couldn’t tell which units were taken out of the market or not.

Tom Caton, who is chief revenue officer for Airdna, said hosts with dozens of listings would disappear off the platform after local protests in American cities. Then the exact same listings would appear again under a dozen different identities.

“It’s interesting. In Europe, Airbnb is professionalizing much more out in the open than it is in the U.S.,” Caton said. “In the U.S., Airbnb likes the idea that people are renting out their own homes.”

Meanwhile, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky has stuck to the line that the company helps the middle-class make ends meet. Over the summer, Airbnb hired former White House National Economic Advisor Gene Sperling to do a report arguing that the company is combating middle-class income stagnation.

The company’s rhetoric has focused on averages or medians, taking the focus away from the high-end segment of the market.

“The sharing economy allows someone in 60 seconds to become an entrepreneur and to make a new income,” Chesky said in an interview with Tim O’Reilly at the Code for America Summit in Oakland a few weeks ago. “It’s the equivalent of a 14 percent raise. They can make another $8,000. That can be the difference between people being in the middle-class or not being in the middle-class.”

Only once has the company done a large-scale cleaning of commercial rentals when it removed 2,000 listings from New York City last year. This was only after New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman forcibly subpoenaed data from the company showing that 6 percent of hosts were generating 37 percent of the revenue.

In the same interview with O’Reilly earlier this month, Chesky acknowledged the issue:

“Is everything on Airbnb perfect and amazing? Not everything is perfect. When we started Airbnb, I believed in Craig Newmark’s idea. He’s the founder of Craigslist. He believed that communities should be open, that they should be democratic, and they should be self-regulating like immune systems. I believed that too and I actually don’t totally believe that anymore. At the time, I believed that we had a reputation system, that if somebody’s bad they’re going to get bad reviews and the system is going to work. But we started realizing that some people were exploiting our platform and there were some more real estate people in cities like San Francisco and New York that were buying up apartments. We didn’t even know the extent of this issue. It really did become an issue. Eighteen months ago, we had to remove a couple thousand apartments. But we have not succeeded because of them. We’ve succeeded in spite of them. The vast majority of Airbnb are regular people. The last thing somebody wants to do is stay in a property-managed apartment that feels like a hotel. Just go to a hotel. The whole point of Airbnb is this feeling of belonging. You get hospitality. You’re staying in a real person’s home. That is the vast majority of what our community is. That’s what I want our community to be.”

However, under the current system, the burden of making sure this is true falls entirely on the four (soon to be six) people working in San Francisco’s enforcement department, who do not have access to accurate or real-time data on the market they are trying to regulate.

Platforms have the ability to make ethical choices for the communities they serve. When there were widespread media reports that children were spending hundreds or thousands of dollars on virtual currency through the iOS app store, Apple added a password security prompt for parents.

Airbnb has never added any kinds of limits like this into its product for the number of days hosted in cities with chronic housing shortages. It says it has too many irregular listings like boats or actual hotels to do so.

What Would Proposition F Change?

- Imposes fines on hosting platforms that list unregistered short-term rental units. (Hosting platforms are currently not penalized for listing unregistered units.)

- Requires hosting platforms and hosts to make quarterly reports of rental nights. (Under the current law, only hosts have to report their activity.)

- Caps the number of hosted nights to 75 per year across the board. (Currently, hosts can do a maximum of 90 days if they’re not there, or an unlimited number of days if they are present.)

- Notifies neighbors and homeowners associations when a short-term rental registration is issued. (Currently, there are no notifications.)

-

- Allows residents access to a legal right of action and entitlement to financial relief if the city doesn’t act on complaints within 90 days.

What Is Different About Legal Liability In Proposition F?

Last month, an essay from occasional host and Eventbrite marketing director Eric Meyerson, who is writing as an individual and isn’t representing his employer, went viral.

But half of the issues Meyerson raises in his Medium essay are actually already in the existing law. You can read the current ordinance here.

Criminal misdemeanors with the potential for jail time? That is in the current law.

(e) Criminal Penalties. Any Owner or Business Entity who rents a Residential Unit for Tourist or Transient Use in violation of this Chapter 41A without correcting or remedying the violation as provided for in subsection 41A.6~!£ilifil shall be guilty of a misdemeanor. Any person convicted of a misdemeanor hereunder shall be punishable by a fine of not more than $1,000 or by imprisonment in the County Jail for a period of not more than six months, or by both. Each Residential Unit rented for Tourist or Transient Use shall constitute a separate offense.

Neighbors getting the ability to take hosts to court? That is in the current law.

(B) An Interested Party who is a Permanent Resident of the building in -which the Tourist or Transient Use is alleged to occur, is a Permanent Resident of a property within 100 feet of the property containing the Residential Unit in which the Tourist or Transient Use is alleged to occur. or is a homeowner association associated with the Residential Unit in which the Tourist or Transient Use is alleged to occur may institute a civil action for injunctive and monetary relief against an Owner or Business Entity if….

Quarterly reporting requirements for hosts? That is in the current law.

(C) Reporting Requirement. To maintain good standing on the Registry, the Permanent Resident shall submit a quarterly report to the Department beginning on January 1. 2016. and on January 1, April 1. July 1, and October 1 of each year thereafter, regarding the number of days the Residential Unit or any portion thereof has been rented as a ShortTerm Residential Rental since either initial registration or the last report, whichever is more recent, and any additional information the Department may require to demonstrate compliance with this Chapter 41A.

There is one big difference though.

Under the current law, neighbors can pursue action in civil court against hosts after about four months if the city hasn’t initiated its own civil proceedings. If they win, they’re entitled to attorneys’ fees and costs of covering the lawsuit.

Under Proposition F, neighbors can pursue action after about 90 days and if they win, they’re entitled to attorney’s fees and damages of between $250 and $1,000 per day. If you want to read the legislation yourself, the text of the bill is here and the relevant section is from page seven to 10.

To be fair, no one can predict how the right to win criminal penalties in court would be used or abused. One of the reasons supervisors like Farrell and Scott Wiener have opposed this proposition is because they’re worried about creating an opening for “drive-by lawsuits.” California already has an extremely litigious culture around land-use with the state’s environment law CEQA getting invoked to block bike lanes and high-speed rail for years.

On the other side, Sara Shortt, who runs the Housing Rights Coalition and organized some of the Google bus protests last year, says the right to injunctive relief is what gives the regulation teeth, especially when Proposition F supporters don’t feel like the city has even enforced its own laws for seven years. They say that filing a lawsuit is so time-consuming and expensive anyway that few people, if any, will actually do it.

The Impact Of Losing A Housing Unit To Full-Time Short-Term Rentals

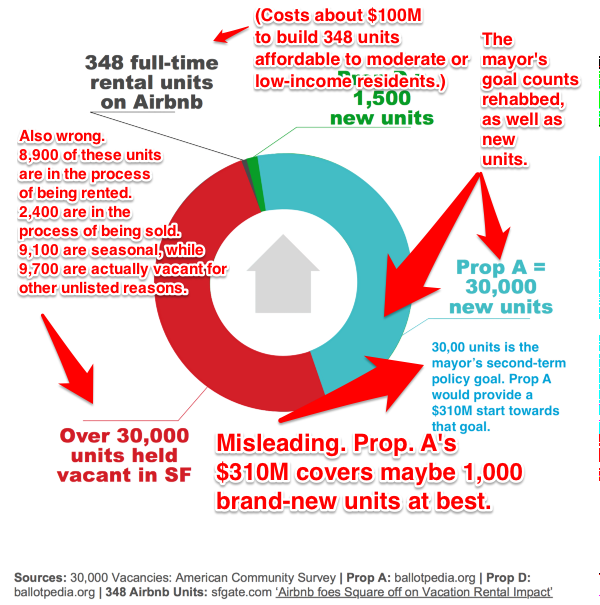

Let’s be conservative and take Airbnb’s estimate: 348 units.

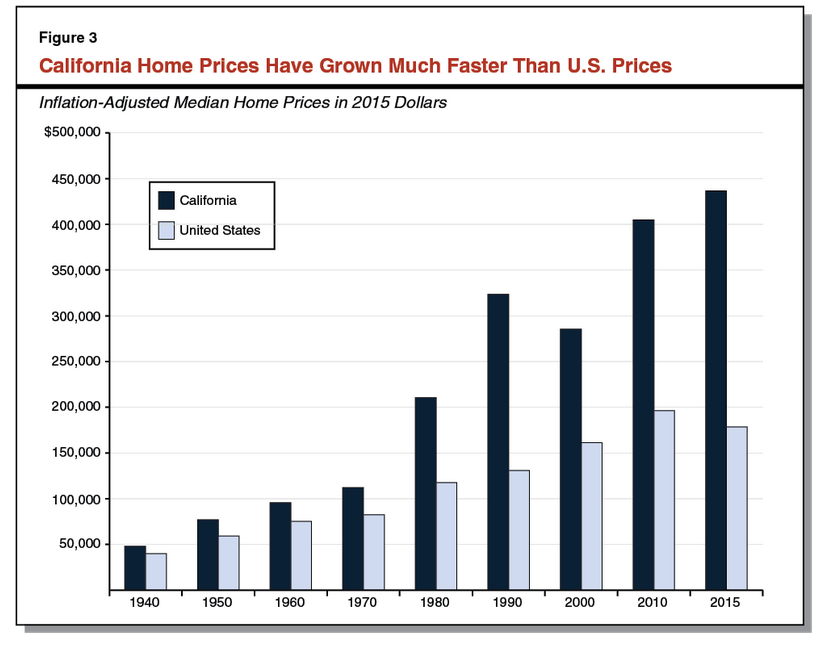

This is a tiny percentage of the city’s overall housing stock at 380,000 units and California’s affordability crisis has been going on since the 1970s. As I’ve written before, there are myriad reasons for the Bay Area housing crisis from restrictive zoning to overseas capital flows to a rapidly widening income distribution that is making it hard for lower- and middle-income to keep up with housing costs.

Californian home prices started splitting from the behavior of the rest of the United States residential real estate in the 1970s. It’s a very long, ongoing crisis that predates the existence of Airbnb by several decades.

However, if San Francisco wanted to construct 348 new units that are affordable to moderate or low-income residents to replace units that are lost, it would cost the city and taxpayers around $100 million. Recent budgets for affordable housing projects range from $250,000 in subsidies per unit to $889,000 per unit in a recently approved 72-unit project on South Van Ness.

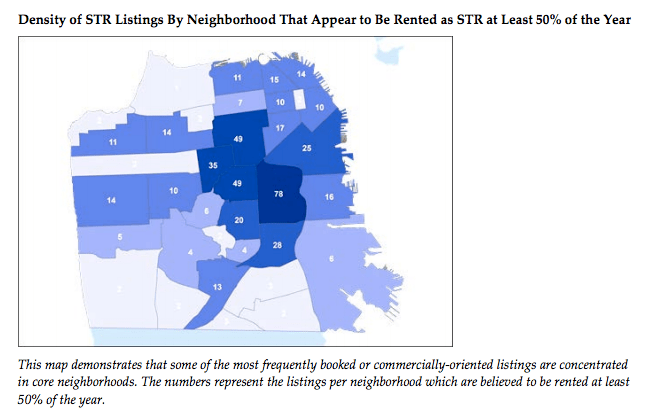

This map is from an SF Planning Department study earlier this year and it shows that the Mission District appears to have the highest amount of permanent short-term rentals in the city. At least 78 units appear to have been rented for more than half the year in the neighborhood.

If the city loses units to permanent short-term rentals, there is immense political pressure to replace them for low- or moderate-income residents. The Latino community of the Mission, which has the highest number of long-term Airbnb rentals in the city, used the Mission Moratorium ballot initiative, or Proposition I, to pressure the city to convert a 72-unit market-rate housing proposal on South Van Ness to affordable housing over the summer. The land alone cost the city $18.5 million, or 1.5 times the amount that Airbnb says its community pays to the city in taxes every year. The total cost of this project is estimated at $64 million, or more than five years of Airbnb tax revenue to the city. That’s a budget of $889,000 per unit.

Moreover, when you lose housing units at lower-priced tiers and do not have a way to finance replacing them, there can be systemic and irreparable consequences.

For example, one of the contributing factors to the emergence of widespread homelessness in San Francisco and New York City in the early 1980s was the destruction of thousands of SRO (or single room occupancy) units. Policy makers and the public misunderstood the role these units played as the housing of last resort for the poor. Between 1975 and 1980, about 6,000 SRO units were converted or demolished in San Francisco.

On top of that, the federal government retreated from public and low-income housing, and community centers that were supposed to in-take mental health patients released through de-institutionalization were under-funded.

U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, who is advocating for Proposition F, was the pro-business and pro-landlord San Francisco mayor who had to deal with the homelessness crisis in the early 1980s. Airbnb had criticized her for having a conflict of interest because her husband owns The Claremont Hotel in the East Bay.

U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, who is a proponent of Proposition F, was a San Francisco supervisor and mayor through the late 1970s and 1980s who had to deal with the emergence of urban homelessness in the city. She also was mayor when rent control was implemented. Amid a housing crisis in the late 1970s, Feinstein passed a weaker rent stabilization ordinance, which pre-empted a stricter version from being passed via ballot initiative. Her husband, Richard Blum, also owns the Claremont Hotel in the East Bay, which Airbnb has criticized as a conflict of interest. (Source: Nancy Wong, CC BY SA-3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

But she was also the mayor whose administration had to open shelters when homelessness initially became visible three decades ago. At first, they thought it was a temporary problem. But it was systemic and required permanent supportive housing.

Thirty years later, “Housing First” policies have been vindicated in other American cities like Salt Lake City as a more humane and less expensive of caring for the homeless, compared relying on emergency medical care and the police. However today, land costs in the Bay Area are so high that it might cost a billion dollars or more to create permanent housing for every homeless person in the city.

And the homeless population’s size? It’s stayed at around 6,000 people for the last decade even though the city has spent $167 million on it annually. A few blocks away from Airbnb’s headquarters, almost one out of every five children at Bessie Carmichael Elementary School is homeless.

More broadly speaking in the United States, cities have historically carried the burden of providing low-income housing, because the immediate surrounding suburbs have practiced exclusionary zoning and fought affordable projects.

A few blocks away from Airbnb’s headquarters, almost one out of every five children at Bessie Carmichael Elementary School is homeless.

In the early 1970s, the wealthy Silicon Valley suburb Los Altos Hills mandated a minimum lot size with one house per one acre. A pair of Mexican-American lawyers then sued on behalf of a Latino group, La Confederacion de la Raza Unida, that had the option of building affordable housing in Los Altos Hills if they could get the density higher than one house per one acre. A California court ruled that even though the minimum lot size meant that lower-income people could not afford to live there, it was not discriminatory. Today, Los Altos Hills still has its lot requirements and its median home price is $4 million.

There are court cases like this scattered literally all over the Bay Area. The Wire creator David Simon even produced an entire six-part series about this dynamic in HBO’s recent “Show Me A Hero.”

More importantly, Latinos began arriving in the Mission in the 1930s around the time that the Federal Housing Administration shut down lending capital to the neighborhood because its racial composition was shifting away from an all-white population. The racialized practices of both the private real estate industry and FHA in the mid-20th century allowed property values to rise much faster in all-white neighborhoods, which has left enduring differentials in household wealth between racial groups that have lasted to this very day.

Today, a similar dynamic is playing out in a different way. The Silicon Valley suburbs are not adding enough housing to match their job growth, which has pushed a critical mass of workers into the urban core in San Francisco and Oakland over the last decade.

Cupertino, for example, approved Apple Campus 2, which will bring an additional 13,000 workers to the city on top of the 16,000 Apple employees that are already there. But the city has pledged to build only 1,400 housing units over the next seven years. A group called Better Cupertino is battling the existing housing commitments because it doesn’t want more children in the suburb’s elite public schools.

“Save Our Schools. Stop Condo-tino.” Old patterns are re-emerging as South Bay cities like Cupertino, where Apple is based, refuse to build adequate amounts of housing. Cupertino has approved Apple Campus 2, which will bring 13,000 more workers to the city, but has only pledged to build 1,400 units over the next seven years. Neighborhood groups like the one staging this protest have opposed more housing because they don’t want more children in the city’s top-performing public schools.

That has created pressure for tech workers to migrate into cities like San Francisco or Oakland. San Francisco houses almost twice as many Bay Area Apple employees as Cupertino does, which is squeezing out working-class communities. They have nowhere to go or afford except for out on the region’s periphery, which induces two or three hour mega-commutes.

If you read studies on generational social mobility, a parent’s transit time is the strongest factor predicting a child’s chance of escaping poverty, according Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s study of five million U.S. family incomes over several decades.

Roberto Hernandez, the activist who collected the signatures for the Mission Moratorium ballot initiative (which I’ll get to later), has got constituents including an 89-year-old sleeping in a closet for $700 a month. Then he’s got Latino families who have been pushed out to Pittsburg in the far East Bay.

“They have to get up at 3 or 4 a.m. in the morning to get to the BART. They jump on the MUNI bus, they drop their kids off at the school, then they jump on another bus to get to work. They’re spending $389 a month on BART and MUNI and they’re making $12 an hour,” he told me over the summer. “What kind of life is that?”

Across the United States, poverty is suburbanizing in places that do not have the infrastructure or ability to serve low-income communities.

To be clear, I am not blaming Airbnb for this. These are just the pre-existing inequities in the American housing system that the company is intersecting with and amplifying.

Airbnb’s Impact On Rents

Again, we don’t have independent data. But an Airbnb-commissioned study suggests that it raises rents slightly by $19 per month or $228 per year in San Francisco.

“Here’s the crazy thing. Now there’s a Proposition — Proposition F. Basically, there are some opponents of Airbnb. They are saying — we are anti-affordable housing. It is pretty weird because the founding story of Airbnb was about allowing people to stay in their homes. Fifty-two percent of our hosts depend on it to pay their rent or mortgage. In many cities, they’re not building supply fast enough. Rents are rising and people are hanging on to be able to keep their homes and they’re looking to Airbnb. That is vast majority of the story. You can literally go on the website and read the profiles and read the stories. The good news is that 100 percent of our homes are available publicly. You can read the stories yourself.”

–Brian Chesky, Airbnb CEO

Land-use, housing and real estate form one of the most morally complex and ambiguous pillars of any society. The central dilemma in the U.S. and U.K. systems is that housing is both a durable good as shelter and an investable asset as a person’s primary form of wealth. That introduces a fundamental tension between policies that maximize property values and conversely, policies that support the goal of affordability.

Any behavior that would increase the cashflow that one can earn from residential housing — from regional employment growth to Airbnb revenue — can at scale get priced into the underlying property value. That would advantage those with the right to the space — mainly the property or homeowners — and disadvantage those who don’t, like tenants or future homebuyers.

Under San Francisco’s law, tenants, who make up two-thirds of the city population, have to abide by their lease agreements around subletting or short-term rentals. Presumably, most of them can’t legally host on Airbnb, because their leases don’t allow it.

Of the seven hundred or so law-abiding hosts who have registered with the city, nine out of 10 are homeowners.

So while it may be true that Airbnb helps many hosts pay their mortgages, that is a statement that only focuses on one segment of the housing market and ignores the impact of higher short-term rental cash flow on the rest.

Why Don’t We Build More Housing?

San Francisco is building housing at the fastest pace in more than two decades.

But a big challenge for San Francisco policy makers is that they have to figure out how to add housing while knowing that at any time, a group of residents can just go and collect 10,000 signatures, put something on the ballot and circumvent them.

That’s what happened a few years ago with 8 Washington, a condo development near the Ferry Building that neighboring residents killed with a ballot initiative. The same group of people — some of whom are Prop. F backers — returned the following year with Prop. B, which requires a vote on any changes to height limits on the waterfront. So now, the entire city has to vote on whether a parking lot should become a 1,500 unit housing development built by the SF Giants.

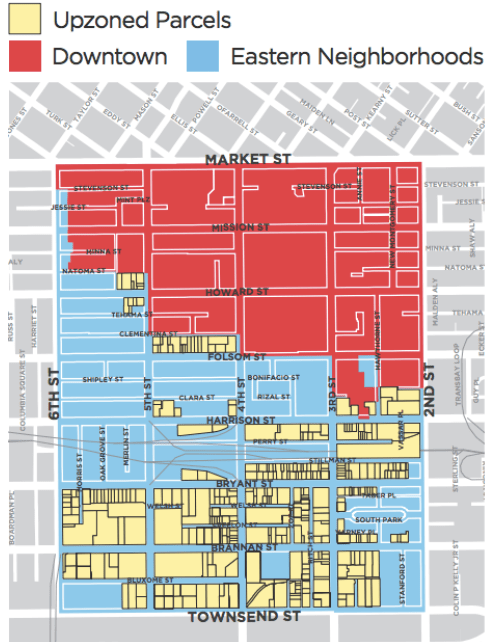

At the current moment, the planning department is in the process of upzoning Central SOMA to add about 50,000 jobs and 11,700 housing units. This is a plan that will affect the burn rates of hundreds, maybe thousands, of startups over the next decade because it will influence the availability of office space. In the spring, sf.citi arranged some meetings to educate the tech community about it. But the only person who showed up was a receptionist, Steve Wertheim, who oversees the plan, told me.

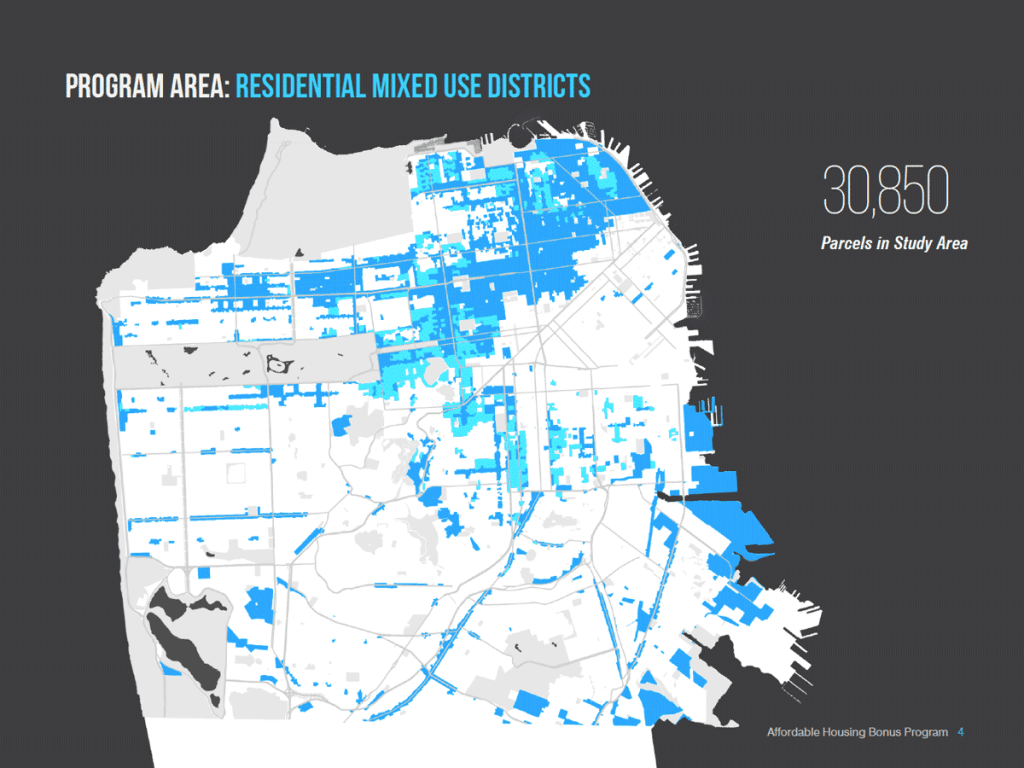

San Francisco is considering increasing housing production in the Western neighborhoods for the first time in recent memory. A density bonus program will award more height to developers if they build more affordable housing.

It is also pushing a density bonus program that will bring housing to the more suburb-like Western neighborhoods by granting a couple more floors to developers in exchange for affordable housing.

But because that land is privately owned, out of the 30,850 parcels of land that city studied for the program, the planning department projects that maybe a few hundred parcels will turn over in the next 20 years and become available to developers. Those will produce another 7,000 to 8,000 extra units. Western neighborhood residents are apparently already organizing against this on Nextdoor.

Residents below showed up to a city-organized meeting this past week to jeer at 1,000 units that may be added to the Outer Sunset over the next 20 years. Meanwhile, between 10,000 and 20,000 people have been moving to the city since 2010.

SF wants to bring density to the westside so of course there’s standing room only at comm meeting. (Civil so far) pic.twitter.com/UvamppWJ17

— Cory Weinberg (@SFBTCory) October 30, 2015

Why Doesn’t SF Just Build Really Tall Buildings?

Upzoning, or raising height, is an intensive process that requires the input of the impacted communities and takes at least a year, if not several.

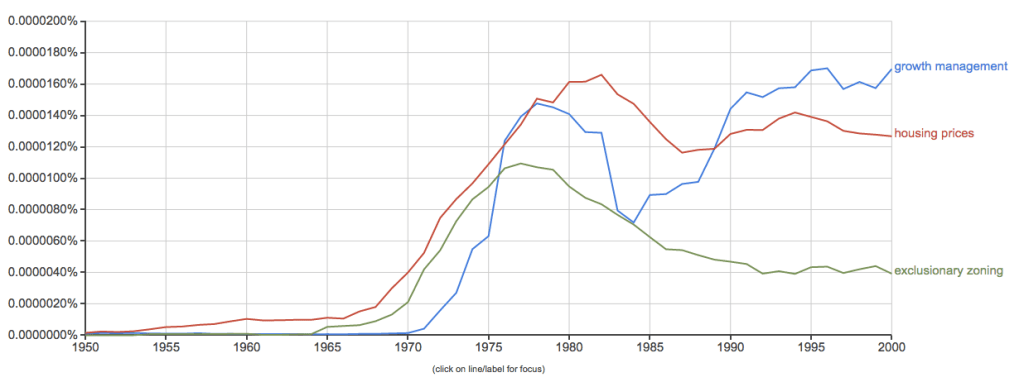

Back in 1975, the California State Supreme court ruled that downzoning someone’s property wasn’t a regulatory taking. Naturally, cities across the state of California then decided to downzone a lot of property because they didn’t have to compensate land owners for reducing financial value of their holdings. California went from issuing one out of every five housing permits in the country in the 1960s to being at the forefront of the growth control movement.

If you use Google Ngram, which graphically tracks the frequency of words and phrases in books, you can see that growth controls became more popular in the mid-1970s. William Fischel, a Dartmouth economist who has spent his entire career studying and practicing zoning, argues that stagflation in the 1970s shifted American perceptions of housing. Homes shifted from being a consumer good to an investment, giving rise to a political class he calls “homevoters.” Today, Airbnb is leveraging “home sharers” as its political class.

Going the other way, or upzoning, requires combing through a neighborhood practically parcel by parcel.

Californian municipal governments do not have a ton of flexibility in managing their revenue sources because new taxes require a two-thirds super-majority vote. 1978’s Proposition 13 fiscalized land use, so local governments have become more reliant on extracting benefits and fees out of developers and new construction for public services.

When you upzone, you are raising the financial value of the underlying land, which becomes an unearned windfall to land owners. If upzoning is not done carefully, it can wipe out existing communities and local institutions that don’t have the capital to keep up as parcels of land turn over to developers.

So upzoning is done conditionally; it’s a fine art of matching the needs and wants of tens of thousands of constituents with whatever is able to financially pencil out for developers.

This is probably a terrible metaphor, but think about it like pricing an IPO. You want it to be priced high enough so that you don’t leave money on the table and see a pop in shares. Likewise, when you upzone land and extract public benefits, you want to get back as much of the unearned increase in land values for voters. But you also still want it to be profitable for developers so they still build stuff and get their 15 or 20 percent return for their investors.

If you leave too much money on the table, your voters can revolt. That’s what’s happening in Redwood City around Box headquarters, where the city allowed a lot of taller, multi-family development but didn’t extract capital for affordable housing. Redwood City residents held candlelight vigils all last week to demonstrate for bigger affordable housing extractions.

The city is upzoning Central SOMA in a plan that it expects to extract about $2 billion in public benefits for affordable housing, transit, childcare, parks and more.

With the Central SOMA rezoning, the city is hoping to get about $2 billion in public benefits for transit, parks, non-profits and affordable housing.

Don’t like it?

Think the upzoning process is too slow?

Okay, well go figure out another place where the city can get $2 billion for infrastructure and affordable housing.

Why Are People Blocking Housing Development?

It varies by jurisdiction. In most of the 101 cities around the Bay Area, tenants are just outnumbered by homeowners, who don’t have a strong reason to add more homes because they’ve already got theirs. In many Californian cities like Palo Alto, there’s almost nothing you can do because you may never mathematically have the votes.

But in San Francisco, it’s different. This is a majority tenant city.

So you’ve got classic NIMBY homeowners, but you also have a tenant base that is open to growth and development so long as it is inclusive.

Part of the reason that development battles here are so divisive is because state and federal funding for affordable housing has dwindled over the last several decades. Last month, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed a bill from San Francisco’s David Chiu that would have provided another $100 million in state tax credits for affordable housing.

Brown was concerned about the state’s budget in the event of a downturn. When he was a much younger California governor in the 1970s, the state’s voters capped their property taxes through Proposition 13. So the state’s revenue base shifted toward income and capital gains taxes, which are more prone to California’s boom-and-bust cycle and predictably put the state government into the red during recessions.

Because there are fewer recurring and stable sources of funding for low-income housing, working-class tenants have taken to blocking or stalling housing on a project-by-project basis to extract concessions out of them for subsidized units.

That’s what’s happening in the Mission, where non-profits are pushing a separate ballot initiative called Proposition I that would stop market-rate housing construction for 18 months.

The idea is to block market-rate developers from acquiring the last large re-developable parcels of land in the neighborhood, so that non-profit developers can try to buy them first. Only parcels that are large enough to support 40 units are eligible for federal programs that finance low-income housing. There are only 13 parcels of this size left in the neighborhood.

The ballot initiative is a kind of realpolitik to pressure concessions out of the city for lower-income residents. In most parts of the United States, zoning is used to exclude uses and poorer communities; but San Francisco neighborhoods like Chinatown, the Tenderloin and the Mission have historically used zoning to preserve lower-income communities in the face of successive waves of capital during boom times.

The Tenderloin actually pulled off what the Mission is trying to do back in the 1980s. It was supposed to be re-developed as Union Square West, but neighborhood activists organized and bought land to hold in perpetuity for low-income residents. The difference is that land was at bargain-basement prices back in the 1980s; now it’s running north of $250,000 per buildable unit.

Since getting the signatures for the Mission Moratorium initiative to pressure Mayor Ed Lee, the city has pledged $50 million to the neighborhood out of a $310 million affordable housing bond if it passes. However, to get to their goal of building 2,400 affordable units in the Mission for the historically Latino base, the neighborhood will need to find at least $600 million in funding.

“Everybody would be happy if we could get 3,000 more affordable units,” Roberto Hernandez, an activist who collected the signatures for the Mission Moratorium ballot initiative, told me over the summer. “Then you could build all the luxury condos that you want.”

(If asking for a unicorn’s worth of affordable housing sounds extreme to you, now you know how crazy bragging about paying $12 million in taxes sounds to anyone who understands anything about housing.)

Hernandez and non-profits like the Mission Economic Development Agency say they are doing this because the current strategies aren’t working. The median household income for Latinos in the neighborhood is $63,641, compared to $102,577 for white households. So the Latino community, which has been in the area since the 1930s, can’t keep up. A report from the legislative analyst last week said that the Latino share of the Mission’s population will decline to less than one-third by 2025 if current trends continue.

City economist Ted Egan released a study arguing that the moratorium won’t relieve displacement pressures and will jeopardize close to 1,500 units in the pipeline over the next two years. Egan said that 97 percent of upper-income residents arriving in the city end up living in existing units.

Tech founders, are, of course, frustrated. They’d like to hire thousands of engineers over the next several years, but the competition for housing is driving up rents and salary costs higher and higher.

And again, the city can’t coerce land owners into selling their property to non-profit developers. So unless the moratorium is permanent, land owners might sit it out until the end because they don’t want to sell at a discount.

What about the 30,000 vacant units?

Let me correct this misleading graphic for you.

Lots of Proposition F opponents have pointed out this figure that there are 30,000 vacant housing units in San Francisco. The number actually comes from American Community Survey data in the U.S. Census.

It is split into four categories:

- Rental units that are in the process of being rented (“for rent”) or units that have been rented, but are not yet occupied (“rented, not occupied”) — about 8,900 units.

- Ownership units that are in the process of being sold (“for sale”) or units that have been sold but are not yet occupied (“sold, not occupied”) — about 2,400 units.

- Units used for seasonal, recreational or occasional use — about 9,100 units.

- Other vacant units not in any of the categories above — about 9,700 units.

The Bay Area’s urban planning think-tank SPUR tried to use the vacant numbers to infer how many units might be taken out of the housing stock last fall. They estimated that only 2.4 percent of the city’s housing stock is seasonal based on surveys of brand-new condo buildings downtown. Even though Airbnb investor Sam Altman and others have insinuated that rent control might lead to vacancy, SPUR studied this and said it was impossible to tell.

But the bigger point is that data on Bay Area real estate markets is of horrifically bad quality.

At the higher-end of the market in suburbs like Palo Alto, there is overseas capital from China flowing into local homes because the property market abroad is slumping. Some of it is for buyers who genuinely want to live and work in Silicon Valley; immigrants have been a vital part of the Valley’s success story over its entire history. But at worst, some of the property is left vacant and none of the peninsula suburban governments are quantifying it. In Atherton, about half of home sales above $5 million are bought by LLCs that conceal the entity of the buyer.

The lack of good data on the market at all levels makes it harder to figure out solutions to the crisis.

At the lower-end of the market out closer to Central California, REO-to-rental is showing up as banks and REITs acquire homes to operate as single-family rentals. Sometimes, they’re the very same entities that offered unsustainable subprime loans to lower-income borrowers, who then ruined their credit on foreclosures.

Then at the very bottom end of the market, even the city’s homeless count is crude. One day every two years, bands of volunteers scour through the city’s streets to visually count how many people appear to be living without shelter.

The lack of good data on the market at all levels makes it harder to figure out solutions to the crisis. No one knows how many tenants genuinely need rent control based on their income and no one knows what levels of affordable housing will really financially pencil out for real estate developers.

To add another layer of opacity is counter-productive. If anything, Airbnb’s investors, who also back companies like Mixpanel and Optimizely, should understand the vital importance of high-quality data is designing well-functioning systems.

What About Reporting Where You Sleep At Night?

There are other U.S. state and municipal governments require you to document and prove where you are in order to qualify for tax benefits.

The state of Florida has zero income taxes. But in order to get this benefit, you must prove that you live there at least 180 days a year. The steps to prove that legally cover everything from changing your mailing address to moving your financial accounts to the state of Florida. But it also includes recording and reporting the days that you spend in the state.

Moreover, if you’re going to use the overnight excess capacity of your home as a revenue-generating business, it seems odd that you wouldn’t expect some privacy trade-offs associated with this decision. This is especially true in San Francisco, which doesn’t have a hard cap across the board; it has a split cap that is different based on whether the host is present or not.

What about rent control? Isn’t it a distortion?

I’ve seen several Prop. F opponents or tech workers allude to rent control being a major source of the housing crisis. It certainly complicates re-developing existing housing, but here are some things to keep in mind.

(This part is kind of in the weeds. Sorry. You can skip ahead unless you’re really interested in the structural problems of the Californian housing market.)

Rent control covers 46 percent of the housing units in San Francisco; it’s very unlikely that it would get voted away. The only major American city to get rid of rent control in recent memory is Boston in the mid-1990s, and that was done through a change in statewide law. That said, the California state legislature has watered down San Francisco’s rent control before, through laws like Costa-Hawkins which banned rent control on single-family homes and on new construction after 1995. Under the current laws, the only politically feasible way to phase it out is to have the city buy rent-controlled units and gradually convert them to income-tested affordable units or community land trusts. This would take a very long time and cost a lot of money.

A majority of economists deride rent control because it can disincentivize production of new housing.

However if you oppose rent control because it is a market distortion, at least consider the other major market distortions in the American housing system.

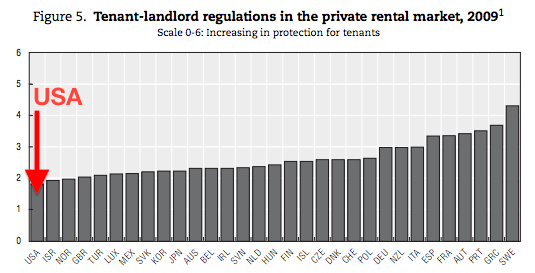

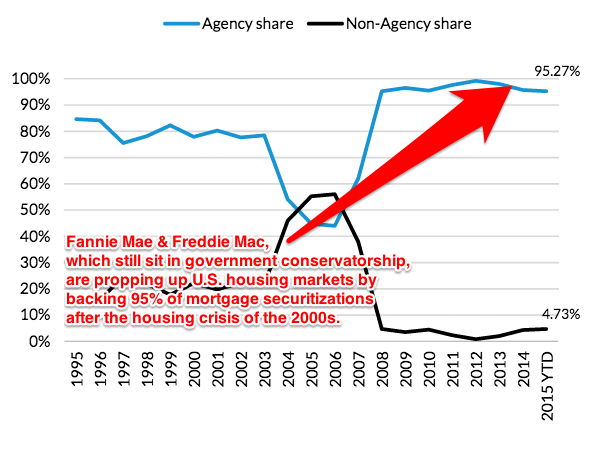

The American approach to housing is laced with an incredible amount of contradictions. The U.S. has the weakest tenant protections of all the OECD countries but has the world’s largest socialized mortgage market with government-sponsored enterprises handling 95 percent of mortgage securitizations.

Then, the ideal of the detached single-family home is based on self-sufficiency and individual property rights, but it is reliant on an enormous and submerged structure of tax subsidies. Moreover, single-family zoning is very much about controlling what other people can do with their property. In the U.S., the right to own property has been separated from the legal right to develop it for about a century.

The 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage

Homeowners, which live in 36 percent of San Francisco’s housing stock, have something that effectively behaves like a price control in the form of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and property tax caps under Proposition 13.

From the perspective of global housing markets, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is a financial instrument that is largely unique to the United States and Denmark. Most other countries have shorter-term, flexible rate mortgages because there is too much credit, interest-rate and early repayment risk associated with such a long duration. The only reason 30-year fixed-rate mortgages exist so widely is because they are backstopped by the GSEs or government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which guarantee $5 trillion in home mortgage debt. Their existence has amounted to an enormous and unquantifiable subsidy in borrowing costs to homeowners over the past 80 years since the Great Depression.

Even though global financial markets price these securities as if they will be backed by the U.S. government in the event of a default, U.S. Congress obviously doesn’t want to add $5 trillion onto the public debt.

But the mortgage market also can’t be privatized either because private insurers only cover about $10 to 15 billion per year, a drop in the bucket compared to the trillions that Fannie and Freddie support. Immediately privatizing the mortgage securitization market might crash American housing markets because borrowing costs would rise sharply.

Federal policy makers haven’t figured out how to design an incentive system to prevent what happened in the mid-2000s from occurring again. In fact, Fannie was created during the Great Depression to support a steady flow of capital into American housing markets, instead the boom and bust dynamic of private financing. So Fannie and Freddie have sat in purgatory and government conservatorship for eight years because U.S. Congress doesn’t know what to do with them.

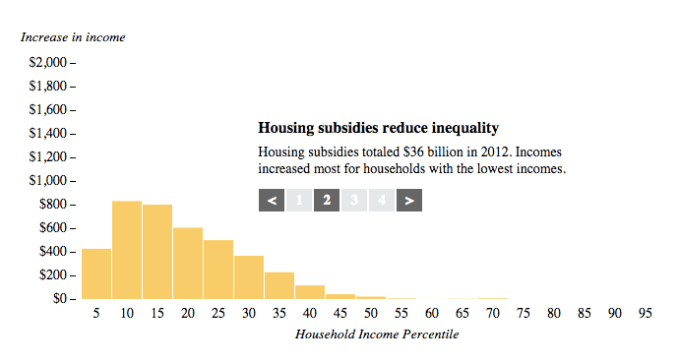

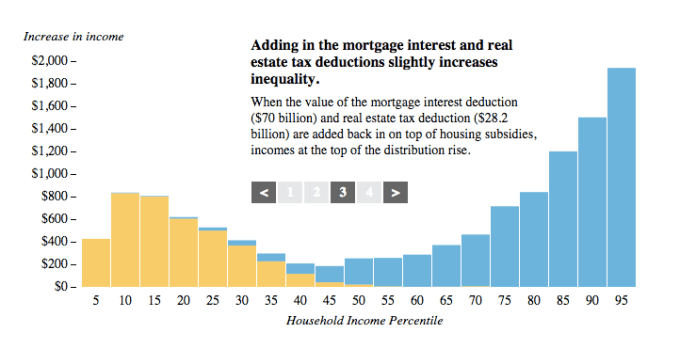

Taxpayer Subsidies to Homeowners Are Much Bigger Than Housing Subsidies For The Poor

Then, if you look at tax subsidies, federal housing policy is regressive. The U.S. federal government spends more than twice as much on tax deductions for middle- and upper-income homeowners than it does on subsidies for lower-income Americans.

Californians make up a little more than 10 percent of the U.S. population, but they receive about one-fifth of the benefits of the mortgage interest tax deduction. That’s because the more expensive or larger a home you buy, the bigger your tax deduction becomes. The mortgage interest tax deduction ends up subsidizing Californians buying more expensive homes than they would otherwise buy.

California’s Property Tax System Favors Seniority

Then if you look at the state level, California’s property tax structure favors older homeowners. Property tax assessments are set at whenever a person bought their home, and rise no more than 2 percent per year after that.

This system was set up in 1978 after stagflation and growth controls sent Californian home prices spiraling higher and higher, with property tax assessments rising in tandem.

Californian voters put an end to this with Proposition 13, but that in turn cemented all other kinds of inequities in the state’s property system. The tax savings ended up being capitalized into even higher home prices. In 1980, a UC Berkeley study found that each dollar decrease in property taxes resulted in a seven dollar increase in property values.

Today, there are huge imbalances as newer homeowners subsidize the cost of public services for older homeowners. In Silicon Valley’s original home of Santa Clara County, homeowners who bought their homes after 1999 cover 78 percent of the county’s residential property tax assessments.

My mother in law purchased her Palo Alto home in 1964, & value is approximately up 9,953%. Prop 13 means taxable value is 3.7% actual value.

— Louis Gray (@louisgray) October 5, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Prop. 13 also encourages land-banking because there’s no strong disincentive to sitting on and doing nothing with land while it appreciates. Property owners’ taxes are capped. That feeds into the strange behavior of the state’s housing market, where prices rise sharply and then plateau, but never go down. When markets cool, land owners simply just withhold supply and wait it out for the next upswing.

Then There’s Zoning

Lastly, if you look at the local level, there are the zoning regulations, which I’ve already written a lot about.

More than 70 percent of the parcels in San Francisco are for single-family homes. Because single-family homes are considered sacred and untouchable, that means that the burden of new housing development falls on the multi-family neighborhoods in the city’s Eastern neighborhoods, which are historically lower-income and have larger minority populations.

But Most Importantly…

The ideal of homeownership was not offered equitably in the many decades after World War II. It was deliberately cut off for minorities in policies that still leave a footprint today in disparate homeownership rates and household wealth levels between blacks, Latinos and whites.

You think you know the racism of redlining. But then you read a description of one of the areas (the center red box). pic.twitter.com/zoNZqV0QUq

— Alexis C. Madrigal (@alexismadrigal) October 12, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

If you want to read a national history of this, it’s here. If you want a local Bay Area version, I have one on how East Palo Alto and Palo Alto were formed in relation to one another. The inequitable residue of these policies are painfully obvious in the fights over the Mission, Oakland and other gentrifying neighborhoods in the United States — which coincidentally happen to be some of Airbnb’s hottest markets.

All of this is to say that wherever you go in the world, housing is a complex public-private system.

The very capitalism-friendly city-state of Singapore is 80 percent public housing. In Japan, the building codes change with successive earthquakes, so property owners have to continuously tear down their buildings and reconstruct them to keep up with the law. This creates a culture where home values actually depreciate like cars. An interesting byproduct of this is that the country can sustain a much higher number of architects per capita. Because Japanese homeowners don’t have to worry about re-sale value, they can construct weird, radically expressive homes.

Germany doesn’t subsidize homeownership so its rate is around 40 percent, compared to the 63.4 percent homeownership rate in the United States. It has incredibly strong tenant protections, which behave like rent control. But Germany also balances this out with a right-to-build embedded in the Constitution, a standard set of zoning codes across the entire nation and a municipal financing system that allocates more capital as a region’s population grows. As a result, they’ve had relatively stable housing prices over the last 25 years.

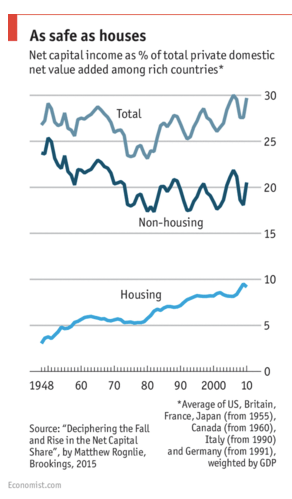

MIT graduate student Matthew Rognlie had one of the most pointed responses to Thomas Piketty’s theory that wealth inequality will keep rising inexorably because the rate of return on capital is greater than overall economic growth. He separated out housing from non-housing investments and showed that it is almost entirely responsible for rising returns on capital.

In contrast, the U.S. and U.K. mix the role of housing as a person’s main store of wealth with its role as a human necessity of shelter. In the post-war period, this was arguably a great thing; cheaply-subsidized land and home ownership cemented the creation of the middle-class.

Today, this ideal has mutated into a tax on productivity in the U.S. and U.K.’s most dynamic cities like London, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. State and local zoning protections and tax benefits hardened around homeownership beginning the 1970s and are now intersecting with a widening income distribution and rapid globalized capital flows in a near zero-interest rate world.

In the United States, both the banking and political systems are structured to favor ever-rising home prices. Almost two-thirds of bank lending portfolios are made of mortgages while most of the political jurisdictions are majority homeowner. This might be totally great, except for the fact that the American system has never adequately covered the flipside of this policy for those who lack the capital to step onto the first rungs of the property ladder. This was a structure that affected minorities and the poor for decades. But now it is affecting the middle-class and younger people of all backgrounds in the U.S.’s most economically productive regions.

If Californians want to slow the unrelenting spiral of upward prices, they would have to do things that I don’t think Californians — especially homeowners — are prepared to do. They would have to reconsider the ideal of the single-family detached home and the zoning that protects it. They would have to reconsider the property tax structure and find a permanent and recurring source of funding to support the service workers and the poor through either outright affordable construction, housing subsidies or living wages. Even the most astute of political observers, Jerry Brown, who was governor of California in the 1970s and is governor today, does not believe this is possible.

So everything — including Prop. F, Prop. I and extra Airbnb cash-flow — is just about re-arranging deck chairs.

What Should You Do?

Both approaches are flawed.

In the current system, the city only has data on seven percent of hosts who are registered. Even though Airbnb is not the cause of the housing crisis, the company has declined to take responsibility in not making the current situation worse by cracking down on obvious commercial rentals or being transparent with data so that the city can do it for them.

The city’s soon-to-be six-person department can only reactively respond to neighbor complaints in order to protect housing from being lost to permanent short-term rentals. Each unit lost causes the city $250,000 to $300,000 in net negative impact, according to city economist Ted Egan.

But Proposition F is also deeply worrying. It opens the door to more neighbor-versus-neighbor lawsuits, which may wipe the market of hosts. It is also a ballot initiative that can only be amended through more ballot initiatives, which isn’t flexible enough for regulating a fast-changing market. The initiative’s backers add that even if they fail today — which looks likely based on polling data — they’ll be back next year with a different version.

If Airbnb had been more transparent and made a good faith effort in helping the city crack down on the commercial end of the market, maybe we wouldn’t be here. But instead, it spent money on those horrible bus ads and billboards.

So here we are.

Featured Image: UmWtd/Shutterstock

Kim-Mai Cutler

https://techcrunch.com/2015/11/03/prop-f/?ncid=rss

Source link