Still, if you were looking forward to having a Rosie scurrying around your abode, feather duster in hand, an Echo feels like a letdown. It just sits there.

There are good reasons that the domestic robot has taken such an uninspiring form. Some are technical. Visualizing a nimble, sure-footed android is easy, but building one is hard. As the Carnegie Mellon professor Illah Nourbakhsh explains in his book “Robot Futures,” it requires advances not only in artificial intelligence but also in the complex hardware systems required for movement, perception and dexterity.

The human nervous system is a marvel of physical control, able to sense and respond fluidly to an ever-changing environment. Achieving such agility with silicon and steel lies well beyond the reach of today’s engineers. Even the most advanced of our current automatons still get flustered by mundane tasks like loading a dishwasher or dusting knickknacks.

Meanwhile, thanks to gains in networking, language processing and miniaturization, it has become simple to manufacture small, cheap computers that can understand basic questions and commands, gather and synthesize information from online databanks and control other electronics. The technology industry has enormous incentives to promote such gadgets. Now that many of the biggest tech companies operate like media businesses, trafficking in information, they’re in a race to create new products to charm and track consumers.

Smart speakers provide a powerful complement to smartphones in this regard. Equipped with sensitive microphones, they serve as in-home listening devices — benign-seeming bugs — that greatly extend the companies’ ability to monitor people’s habits. Whenever you chat with a smart speaker, you’re disclosing valuable information about your routines and proclivities.

Beyond the technical challenges, there’s a daunting psychological barrier to constructing and selling anthropomorphic machines. No one has figured out how to bridge what computer scientists term the “uncanny valley” — the wide gap we sense between ourselves and imitations of ourselves. Because we’re such social beings, our minds are exquisitely sensitive to the expressions, gestures and manners of others. Any whiff of artificiality triggers revulsion. Humanoid robots seem creepy to us, and the more closely they’re designed to mimic us, the creepier they are. That puts roboticists in a bind: The more perfect their creations, the less likely we’ll want them in our homes. Lacking human characteristics, smart speakers avoid the uncanny valley altogether.

Although they may not look like the robots we envisioned, smart speakers do have antecedents in our cultural fantasy life. The robot they most recall at the moment is HAL, the chattering eyeball in Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic “2001: A Space Odyssey.” But their current form — that of a stand-alone gadget — is not likely to be their ultimate form. They seem fated to shed their physical housing and turn into a sort of ambient digital companion. Alexa will come to resemble Samantha, the “artificially intelligent operating system” that beguiles the Joaquin Phoenix character in the movie “Her.” Through a network of speakers, microphones and sensors scattered around our homes, we’ll be able to converse with our solicitous A.I. assistants wherever and whenever we like.

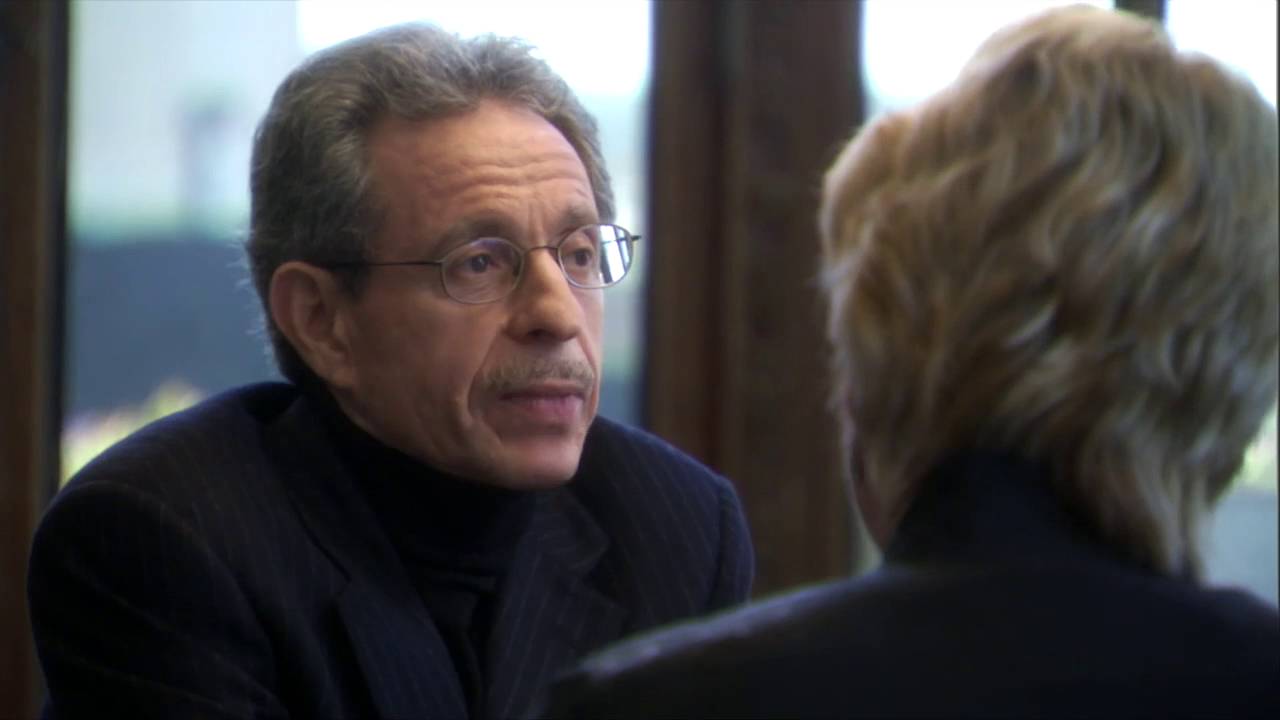

Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook C.E.O., spent much of last year programming a prototype of such a virtual agent. In a video released in December, he gave a demo of the system. Walking around his Silicon Valley home, he conducted a running dialogue with his omnipresent chatbot, calling on it to supply him with a clean T-shirt and toast bread for his breakfast, play movies and music, and entertain his infant daughter. Hooked up to cameras with facial-recognition software, the digitized Jeeves also acted as a sentry for the Zuckerberg compound, screening visitors and unlocking the gate.

Whether real or fictional, robots hold a mirror up to society. If Rosie and her kin embodied a 20th-century yearning for domestic order and familial bliss, smart speakers symbolize our own, more self-absorbed time.

It seems apt that as we come to live more of our lives virtually, through social networks and other simulations, our robots should take the form of disembodied avatars dedicated to keeping us comfortable in our media cocoons. Even as they spy on us, the devices offer sanctuary from the unruliness of reality, with all its frictions and strains. They place us in a virtual world meticulously arranged to suit our bents and biases, a world that understands us and shapes itself to our desires. Amazon’s decision to draw on classical mythology in naming its smart speaker was a masterstroke. Every Narcissus deserves an Echo.

By NICHOLAS CARR

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/09/opinion/sunday/household-robots-alexa-homepod.html

Source link