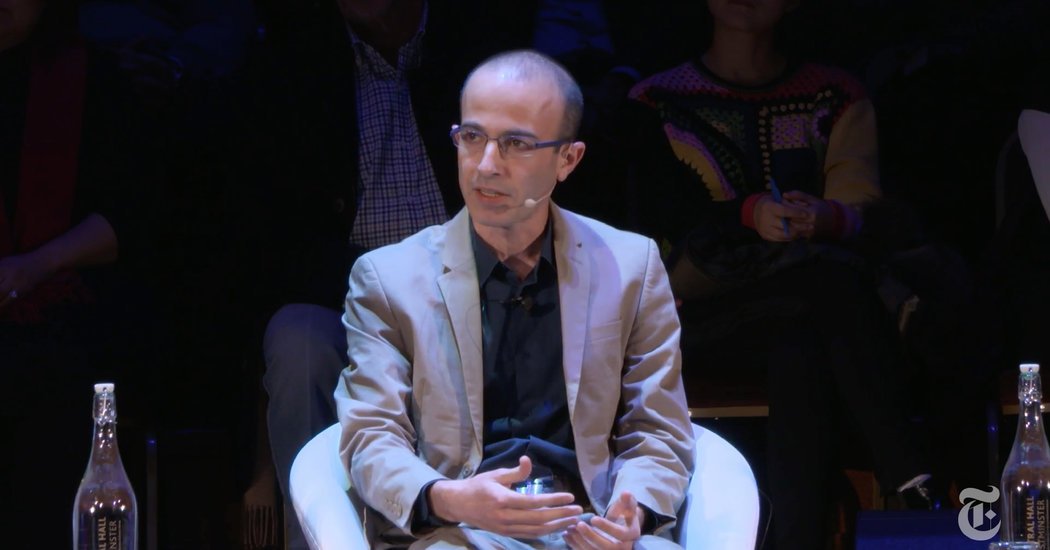

“Once you have an external outlier that understands you better than you understand yourself, liberal democracy as we have known it for the last century or so is doomed,” Mr. Harari predicted.

“Liberal democracy trusts in the feelings of human beings, and that worked as long as nobody could understand your feelings better than yourself — or your mother,” he said. “But if there is an algorithm that understands you better than your mother and you don’t even understand that this is happening, then liberal democracy will become an emotional puppet show,” he added. “What happens if your heart is a foreign agent, a double agent serving somebody else, who knows how to press your emotional buttons, who knows how to make you angry, how to make you bold, how to make you joyful? This is the kind of threat we’re beginning to see emerging today, for example in elections and referendum.”

Technology will be a new tool for discrimination — not against groups but individuals.

In the 20th century, discrimination was used against entire groups based on various biases. It was fixable, however, because those biases were not true and victims could join together and take political action. But in the coming years and decades, Mr. Harari said, “we will face individual discrimination, and it might actually be based on a good assessment on who you are.”

If algorithms employed by a company look up your Facebook profile or DNA, trawl through school and professional records, they could figure out pretty accurately who you are. “You will not be able to do anything about this discrimination first of all because it’s just you,” Mr. Harari said. “They don’t discriminate against your being because you’re Jewish or gay, but because you’re you. And the worst thing is that it will be true. It sounds funny, but it’s terrible.”

Time is ‘accelerating.’

It took centuries, even thousands of years, for us to reap the rewards of decisions made by our forebears, for example, growing wheat that led to the agricultural revolution. Not anymore.

“Time is accelerating,” Mr. Harari said. The long term may no longer be defined in centuries or millenniums — but in terms of 20 years. “It’s the first time in history when we’ll have no idea how human society will be like in a couple of decades,” he said.

“We’re in an unprecedented situation in history in the sense that nobody knows what the basics about how the world will look like in 20 or 30 years. Not just the basics of geopolitics but what the job market would look like, what kind of skills people will need, what family structures will look like, what gender relations will look like. This means that for the first time in history we have no idea what to teach in schools.”

Leaders focus on the past because they lack a meaningful vision of the future.

Leaders and political parties are still stuck in the 20th century, in the ideological battles pitting the right against the left, capitalism versus socialism. They don’t even have realistic ideas of what the job market looks like in a mere two decades, Mr. Harari said, “because they can’t see.”

“Instead of formulating meaningful visions for where humankind will be in 2050, they repackage nostalgic fantasies about the past,” he said. “And there’s a kind of competition: who can look back further. Trump wants to go back to the 1950s; Putin basically wants to go back to the Czarist Empire, and you have the Islamic State that wants to go back to seventh-century Arabia. Israel — they beat everybody. They want to go back 2,500 years to the age of the Bible, so we win. We have the longest-term vision backwards.”

‘There is no predetermined history.’

“We’re now living with the collapse of the last story of inevitability,” he said. The 1990s weres flush with ideas that history was over, that the great ideological battle of the 20th century was won by liberal democracy and free-market capitalism.

This now seems extremely naïve, he said. “The moment we are in now is a moment of extreme disillusionment and bewilderment because we have no idea where things will go from here. It’s very important to be aware of the downside, of the dangerous scenarios of new technologies. The corporations, the engineers, the people in labs naturally focus on the enormous benefits that these technologies might bring us, and it falls to historians, to philosophers and social scientists who think about all of the ways that things could go wrong.”

In a complex, interconnected world, morality needs to be redefined.

“To act well, it’s not enough to have good values,” Mr. Harari said. “You have to understand the chains of causes and effects.”

Stealing, for example, has become so complicated in today’s world. Back in biblical times, Mr. Harari said, if you were stealing, you were aware of your actions and their consequences on your victim. But theft today could entail investing — even unwittingly — in a very profitable but unethical corporation that damages the environment and employs an army of lawyers and lobbyists to protect itself from lawsuits and regulations.

“Am I guilty of stealing a river?” asked Mr. Harari, continuing his example. “Even if I’m aware, I don’t know how the corporation makes its money. It will take me months and even years to find out what my money is doing. And during that time I’ll be guilty of so many crimes, which I would know nothing about.”

The problem, he said, is understanding the “extremely complicated chains of cause and effect” in the world. “My fear is that homo sapiens are not just up to it. We have created such a complicated world that we’re no longer able to make sense of what is happening.”

By KIMIKO de FREYTAS-TAMURA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/19/world/europe/yuval-noah-harari-future-tech.html

Source link