The backlash has been fierce.

“I imagined I’d raise the alarm,” Dr. Kosinski said in an interview. “Now I’m paying the price.” He’d just had a meeting with campus police “because of the number of death threats.”

Advocacy groups like Glaad and the Human Rights Campaign denounced the study as “junk science” that “threatens the safety and privacy of LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ people alike.”

The authors have “invented the algorithmic equivalent of a 13-year-old bully,” wrote Greggor Mattson, the director of the Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies Program at Oberlin College. He was one of dozens of academics, scientists and others who picked apart the study in blog posts and Tweet storms.

Some argued that the study is just the latest example of a disturbing technology-fueled revival of physiognomy, the long discredited notion that personality traits can be revealed by measuring the size and shape of a person’s eyes, nose and face.

The researchers have their defenders as well, among them LGBTQ Nation, which criticized Glaad for failing to understand “how science works.” But even they have been unable to agree on precisely what the tool has shown.

At the heart of the controversy is rising concern about the potential for facial analysis to be misused and for findings about its effectiveness to be distorted.

Indeed, few of the claims made by researchers or companies hyping its potential have been replicated, said Clare Garvie of Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology.

“At the very best, it’s a highly inaccurate science,” she said of promises to predict criminal behavior, intelligence and other character traits from faces. “At its very worst, this is racism by algorithm.”

Teaching a Machine to ‘See’ Sexuality

Dr. Kosinski and Mr. Wang began by copying, or “scraping,” photos from more than 75,000 online dating profiles of men and women in the United States. Those seeking same-sex partners were classified as gay; those seeking opposite-sex partners were assumed to be straight.

Some 300,000 images were whittled down to 35,000 that showed faces clearly and met certain criteria. All were white, the researchers said, because they could not find enough dating profiles of gay minorities to generate a statistically valid result.

The images were cropped further and then processed through a deep neural network, a layered mathematical system capable of identifying patterns in vast amounts of data.

Dr. Kosinski said he did not build his tool from scratch, as many suggested; rather, he began with a widely used facial analysis program to show just how easy it would be for anyone to pull off something similar.

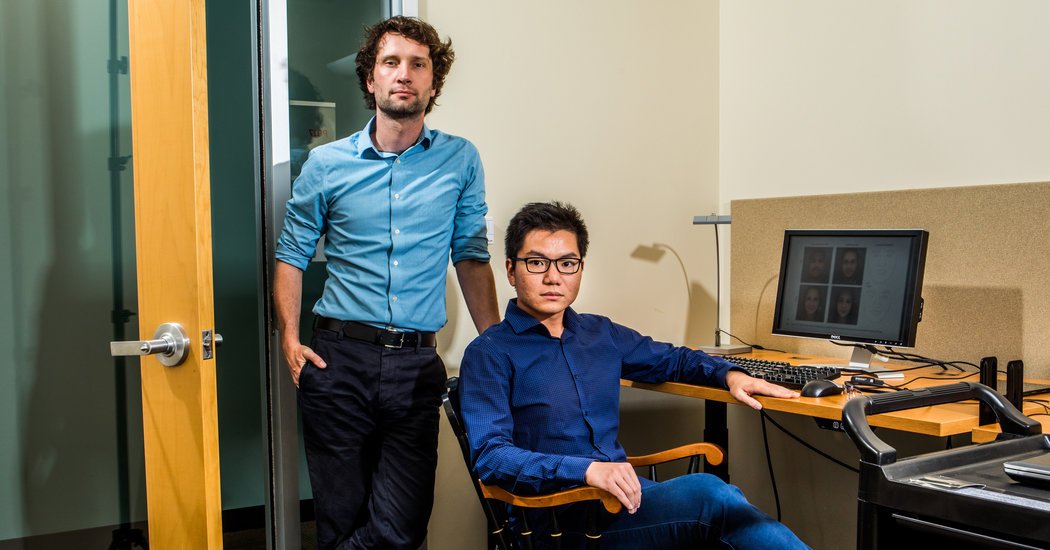

Credit

Michal Kosinski and Yilun Wang

The software extracts information from thousands of facial data points, including nose width, mustache shape, eyebrows, corners of the mouth, hairline and even aspects of the face we don’t have words for. It then turns the faces into numbers.

“We showed that this model produces slightly different numbers for gay and straight faces,” Dr. Kosinski said.

The authors were then ready to pit their prediction model against humans in what would become a notorious gaydar competition. Both humans and machine were given pairings of two faces — one straight, one gay — and asked to pick who was more likely heterosexual.

The participants, who were procured through Amazon Mechanical Turk, a supplier for digital tasks, were advised to “use the best of your intuition.” They made the correct selection 54 percent of the time for women and 61 percent of the time for men — slightly better than flipping a coin.

Dr. Kosinski’s algorithm, by comparison, picked correctly 71 percent for of the time for women and 81 percent for men. When the computer was given five photos for each person instead of just one, accuracy rose to 83 percent for women and 91 percent for the men.

After the study was referenced in an article in The Economist, the 91 percent figure took on a life of its own. News headlines “made it sound almost like an X-ray that can tell if you’re straight or gay,” said Dr. Jonathan M. Metzl, director of the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University.

Yet none of the scenarios remotely resembled a scan of people “in the wild,” as Ms. Garvie put it. And when the tool was challenged with other scenarios — such as distinguishing between gay men’s Facebook photos and straight men’s online dating photos — accuracy dropped to 74 percent.

There’s also the issue of false positives, which plague any prediction model aimed at identifying a minority group, said William T.L. Cox, a psychologist who studies stereotypes at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Let’s say 5 percent of the population is gay, or 50 of every 1,000 people. A facial scan that is 91 percent accurate would misidentify 9 percent of straight people as gay; in the example above, that’s 85 people (0.91 x 950).

The software would also mistake 9 percent of gay people as straight people. The result: Of 130 people the facial scan identified as gay, 85 actually would be straight.

“When an algorithm with 91 percent accuracy operates in the real world,” Dr. Cox said, “almost two-thirds of the times it says someone is gay, it would be wrong.”

He noted in an email that “the algorithms were only trained and tested on white, American, openly gay men (and white, American, presumed straight comparisons),” and therefore probably would not have broader implications.

What a Face Reveals

Regardless of effectiveness, the study raises knotty questions about perceptions of sexual orientation.

Nicholas Rule, a psychology professor at the University of Toronto, also studies facial perception. Using dating profile photos as well as photos taken in a lab, he has consistently found that photos of a face provide clues to all kinds of attributes, including sexuality and social class.

“Can artificial intelligence actually tell if you’re gay from your face? It feels weird — it feels like physiognomy,” he said.

“I still personally sometimes feel uncomfortable, and I have to reconcile this as a scientist — but this is what the data shows,” said Dr. Rule, who is gay.

That is not to say that all LGBTQ people have the similar facial features, or even that there are only two kinds of sexuality, he said. But to pretend that sexual orientation is invisible “suffocates our ability to approach inequity.”

Given that the Stanford study was based on dating profile photos — which may contain all kinds of additional hints about preferences — the results should be taken with “not just a grain, but a tablespoon of salt,” he added.

Credit

Michal Kosinski and Yilun Wang

Dr. Kosinski is no stranger to attention. In 2013, he published a study that showed that Facebook “likes” reveal unexpected personal attributes.

Liking curly fries, for example, was a reliable predictor of higher than average intelligence. Liking Wu-Tang Clan was a tip-off to male heterosexuality. All of our online likes, Dr. Kosinski said, have left us vulnerable to microtargeting by political candidates, companies and others with nefarious intentions.

Within several weeks of publication, Facebook had changed its default settings, keeping likes private. “It’s very similar” to the controversy over his current project, he said. “I was basically trying to warn people. People didn’t take it seriously.”

A major difference, though, is that Dr. Kosinski did not attempt to explain why “liking” curly fries indicated intelligence. It was simply a pattern identified by a machine.

To account for a link between appearance and sexuality, Dr. Kosinski went further, drawing on what his study called “the widely accepted prenatal hormone theory (P.H.T.) of sexual orientation,” which “predicts the existence of links between facial appearance and sexual orientation” determined by early hormone exposure.

The notion that it’s “widely accepted” was quickly disputed.

“That theory is a mess,” said Rebecca Jordan Young, chairwoman of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Barnard University, who wrote a book on P.H.T. “There’s more contradictory and negative data than there is positive.”

Even many experts who are supportive of the theory, said they could not see how a study of self-selected dating photos made the case that gay people have gender- atypical faces, let alone a theory that attributes distinctive features to hormones.

The discussion of P.H.T. made the authors sound out of touch, said Dr. Cox: “Most sex scientists agree that there is no single cause to sexual orientation.”

So What Did the Machines See?

Dr. Kosinski and Mr. Wang say that the algorithm is responding to fixed facial features, like nose shape, along with “grooming choices,” such as eye makeup.

But it’s also possible that the algorithm is seeing something totally unknown.

“The more data it has, the better it is at picking up patterns,” said Sarah Jamie Lewis, an independent privacy researcher who Tweeted a critique of the study. “But the patterns aren’t necessarily the ones you think that you they are.”

Tomaso Poggio, the director of M.I.T.’s Center for Brains, Minds and Machines, offered a classic parable used to illustrate this disconnect. The Army trained a program to differentiate American tanks from Russian tanks with 100 percent accuracy.

Only later did analysts realized that the American tanks had been photographed on a sunny day and the Russian tanks had been photographed on a cloudy day. The computer had learned to detect brightness.

Dr. Cox has spotted a version of this in his own studies of dating profiles. Gay people, he has found, tend to post higher-quality photos.

Dr. Kosinski said that they went to great lengths to guarantee that such confounders did not influence their results. Still, he agreed that it’s easier to teach a machine to see than to understand what it has seen.

The study is on still on track to be published by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, though no date has been set. The paper had already made its way through the official peer review process before unofficial reviewers began ripping it to shreds.

A representative of the American Psychological Association, which manages the journal, denied that the study was placed under “ethical review” due to the uproar, as some reports suggested, though she said that an additional step involving paperwork was taken.

Dr. Kosinski’s reputation may be permanently damaged, he said, but he has no regrets. Officials in a country where homosexuality is criminalized someday soon may turn to facial analysis to identify gay men and women.

“The question is, can you live with yourself if you knew it’s possible and you didn’t let anyone know?” he asked.

By HEATHER MURPHY

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/09/science/stanford-sexual-orientation-study.html

Source link