Modern Money Network: Humanities Division

*Money on the Left: Word, Image, Praxis*

Aesthetics & Abstraction

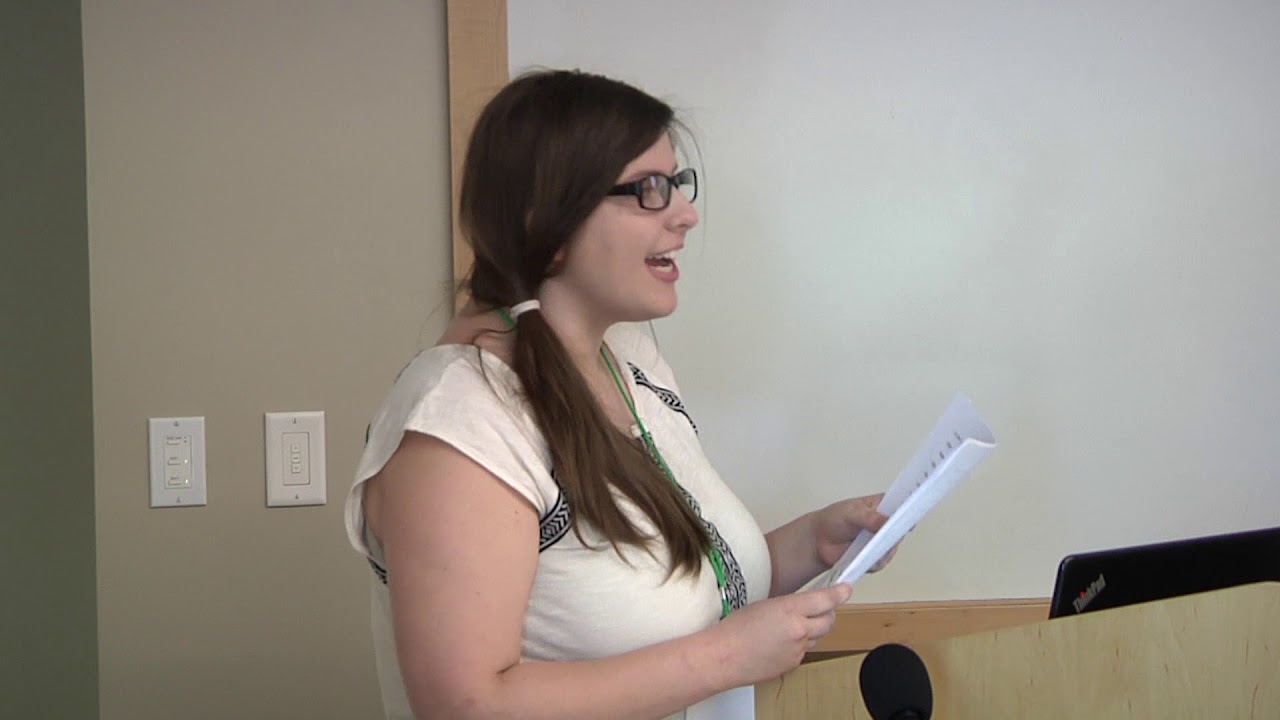

Rachel Cox, “Not So-OK KO: Neoliberal Anxieties in Current Televised Animation”

Modern monetary theory, in addition to providing a different approach to understanding economics, explicitly critiques the more traditional, neoliberal worldview. Both views come with different aesthetic implications, as explored in modern monetary aesthetic theory. In general, because neoliberalism has an anxious relationship of denial towards abstraction, aesthetic abstraction is largely suppressed. However, this relationship is further complicated in the medium of children’s animation, wherein abstraction is built into the constructed, animated worlds. In this talk, I will look at one of the ways that abstraction is simultaneously embraced (in the bodies of the characters) and aggressively suppressed (in the worlds that the cartoons take place) in contemporary televised children’s cartoons.

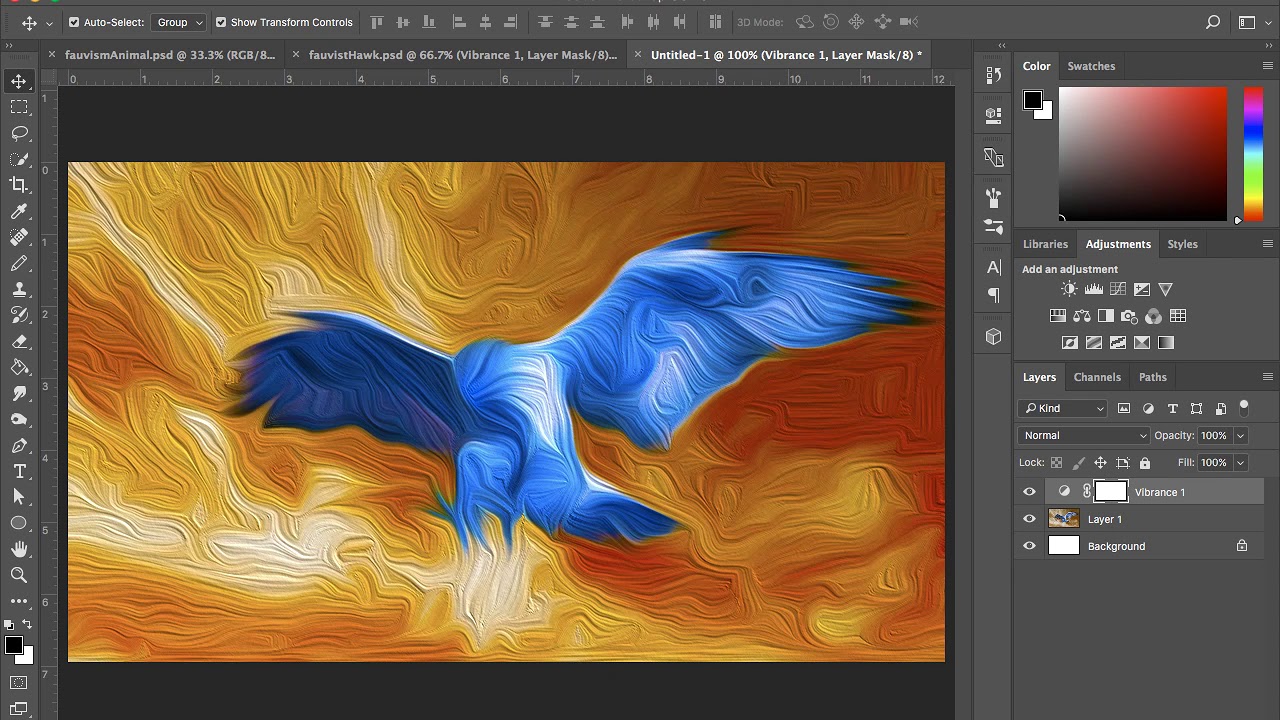

Michael McDowell, “The Neoliberal, Austerity Money-Physics in the Dystopian Survival Game, The Flame in the Flood”

The Flame in the Flood (2017) was released by independent game developer The Molasses Flood. The game sets the player in control of a protagonist on the river of a post- apocalyptic landscape. The player navigates through this landscape but can never actually beat the game: no matter how good the player is, the protagonist always ends up dead. The game, in its visual and musical constructions of place and setting, makes explicit the inherent tensions in Modernity. The game is a digitally-distributed entertainment media that invokes pre-modern folk sensibilities in music and gameplay, the artistic style of the game’s lead artist Scott Sinclair is at once realistic and detailed while also grotesque and gothic, and the game was funded and distributed through crowd sourcing and independent game and music networks while relying on traditionally capitalist ways of selling the game to players. What’s most notable for this conference is the game’s embrace of neoliberal money- physics to create such a dystopian playground: every action in the game, from levels of thirst to the amount of sickness a player is enduring, is quantified and itemized in a way that adheres to a liberal money economic system. The player’s character, we’re told, must die because the developers simply don’t have the mechanics to provide another outcome. If a player, constrained by the rules of the game constructed rather arbitrarily by the designers, can play in such a dystopian sandbox with austerity, constrained game mechanics, what does that say about the possibilities of play in a system that understands boundless, public ideas of money? If money plays by the will of the market due to natural law, why does a game that creates the ideal liberal austerity landscape look like such an awful place to inhabit?

Maxximilian Seijo, “Inglorious Basterds: Nazi Desire Fully Employed”

Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 film Inglorious Basterds sketches an alternate history for the end of WWII and the defeat of the Nazis. In retelling this history, the film avows specific aesthetic and narrative structures that allude to a desire for the figure of the Nazi. Where other forms of media typically deny this persistent desire, Inglorious Basterds embraces it in a Baroque sensationalism. In this paper, I will argue that this desire emanates from a particular economic moment in American life in which money’s boundlessness was utilized: the WWII mobilization. The mobilization enabled the lowest unemployment rate in the history of the United States, and marked the triumph of the “greatest generation” of Americans serving in the factories or on the front lines. This triumph is predicated on the Nazi enemy. Without Nazism, the mass-unemployment of the depression would have lingered into the future. Hinting at this connection, the film makes specific overtures to the nature of employment “obligations” in relationship to fighting Nazism. Looking closely at the film, I reveal how it expresses an unconscious dependence upon the Nazi villain. What is more, I shall contend that the film makes evident this desire for the Nazi through its braiding of cinema writ large with the existence of Nazism. Without the Nazi villain, we lose the cinema. In our desire for employment, we create Nazis on screen that stimulate our desire for the Nazi enemy. Paradoxically, the Nazi form is a form we create to grasp for employment in a quest for social care. As an evocative depiction of this multi-generational quest, Inglorious Basterds discloses and implicates spectators in this repressed desire and permits us to reorganize our political and aesthetic economies around social provisioning rather than war.

@moneyontheleft

https://www.facebook.com/moneyontheleft/

http://modern-money-humanities.webflow.io/

Source