Philosophy Overdose

Daniel Dennett and Tamar Gendler discuss Dan’s new book “Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking”, as well as related issues regarding the nature of thought, argumentation, and thought experiments. They spend much time discussing thought experiments, especially Frank Jackson’s famous knowledge argument (also called Mary’s Room), which is a famous argument in philosophy involving a color deprived scientist named Mary that challenges reductive materialism/physicalism.

This talk is from Bloggingheads TV.

Source

Oh, fun. The beginning was hilarious. I'm in for an awkward discussion. 🙂

I'm sure Dan will be informative nonetheless.

Thanks for the upload!

Dan Dennett is an open source of comprehension. Surely, you want to watch this discussion!

Where's the rest?

I figured that Frank Jackson meant all known things about color, but that it later had erred in concluding that Mary's direct exposure to those facts wasn't a physical one.

If something strikes an unstimulated part of my brain for the first time, that doesn't seem to lend itself to the idea that later stimulating it means that the stimulation wasn't physical.

You be sure to let me know if and when you get that last seven minutes!:)

I did really appreciate this very much, though. Thank you!

*those

I'm a fan of both these philosophers, but Gendler backs Dennett into many corners here that I don't think he successfully wriggled out of. Not that there aren't good responses to Gendler's questions, but her objections seem to catch Dennett on details he wasn't prepared to counter. Great interview!

This debate is absolutely cracking, shame the end is missing though.. Would anyone know where I might be able to find it?

Hot

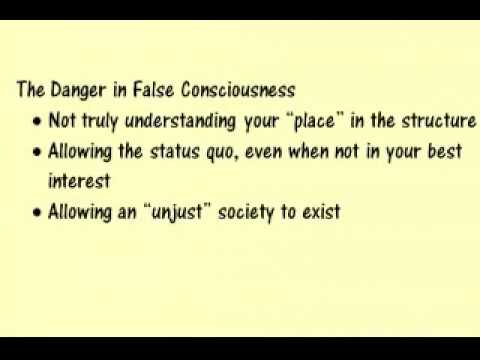

Surely…haha….a simpler refutation of Mary the Colour Scientist as an argument for non-physical facts is just that it begs the question. If seeing a colour were a physical fact, as per eliminative materialism, then someone raised without colour experience could not know all physical facts about colour. This does, however, stretch the interpretation of the word "fact". Often we use the word to mean linguistically expressible ideas. So another version of the same refutation would simply be to acknowledge that she could know all the relevant physical facts about colour, but she has not assumed all possible physical states with regard to colour, which we call the experience of it. None of this sheds light on materialism, dualism or idealism, it's just a semantic game.

In this sense, I think most of Dennett's suggestion that new sensory experience can just be learned by someone if they learned enough facts is unnecessary and probably wrong. The idea that Mary could identify three coloured discs of red, green and blue seems utterly absurd, no matter how much she had studied facts about colour. How could she? She can only learn which colours are which by associating the particular brain state (which equals her experience of it, according to eliminative materialism) with a word told to her: "That's blue". She would be able to sort colours, perhaps, by comparing their sensory effects, but not categorize them.

The only way this could be different is if we assume that the "sum total of the facts about colour" that she knows includes her own neurological correlates of each colour, which is possible only by their firing, and thus "producing" the experience itself, in which case we're just redefining "knowing the facts" to include "having experience". Being able to draw a detailed map of exactly which parts of her brain would fire if she saw blue would be no substitute for having assumed that physical condition herself.

Dennett describes people precluding such methods of peeking into real experience in the thought experiment (like rubbing her eyes or dreaming in colour). We can still just be biological machines correlating different physical states, including the pattern of pressure waves when someone says the name of a colour.

Similarly, we can reverse the experiment, even make it more extreme – imagine someone suffering from a neurological condition that strips them of their sensory experience, rendering them without sight, hearing, touch, etc., and – to make it absolute – even making it impossible for them to recall sensory experiences. I would submit that there are two possibilities: 1) they will still know all the facts (linguistic constructions) they used to know about all the experiences they had, that sunny days felt warm and icecream was sweet, but they can't directly experience them or remember what it was like. Or 2) the condition of knowing such facts as "icecream is sweet" could require a minimal recall of some kind, even just the sound of that statement in the mind (a recall/reconstruction of hearing?), in which case even propositional constructions are "experiential", and stripping someone of all experiential content essentially renders them unconscious.

Either way, something has changed, something has been lost, a category of information is missing, but none of this tells us whether it's ineffable mental stuff or physics. Empirical neurology, on the other hand, seems to be telling us which it is.

Tamar Gendler is great. She had some very insightful and interesting remarks.

This woman's voice is incredibly annoying.

Tamar Gendler is a hot Jewish MILF.

I suspect the use of "surely" to paper over an insufficient argument may be more common in academia than general argument. Law has the idea of "taking judicial notice" to make a factual conclusion based on commonly known or easily researched facts (like post offices being busier during normal business hours). Having to argue that point becomes tiresome and vulnerable to dishonest attacks.

Good stuff.